Adams Family Finds Strength in Community Support as Justin and Tara Recover from Serious Injuries

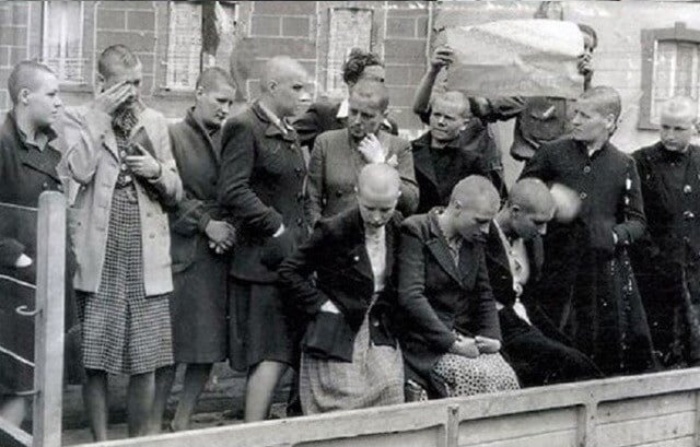

When France was liberated from Nazi occupation in 1944, jubilation quickly turned into judgment. Across the country, thousands of women were accused of maintaining relationships—whether forced, coerced, or voluntary—with German soldiers during the war. For this, they were publicly shamed, their heads shaved as a mark of disgrace. It was a symbolic punishment that spread rapidly through liberated towns, seen as a form of purification after years of occupation.

From the days of the guillotine, France had a long history of public retribution. But after the war, death sentences were often replaced by social humiliation. How much more humane this was remains open to debate. The spectacle of public head-shaving became a substitute for execution—a display meant to reclaim national pride through the humiliation of individuals.

The woman in one of the most famous wartime photographs was believed to have been a prostitute who had served German soldiers. Her shaved head, a visible stigma, was intended to announce her supposed betrayal to all who saw her. Yet many of those punished were not collaborators by choice. Historians have since noted that numerous women were coerced or forced into such relationships under occupation, trapped between survival and condemnation. Despite this, they became the most visible targets of post-liberation revenge.

Between 1943 and early 1946, more than 20,000 French women were publicly humiliated in this way. Age, class, or circumstance offered no protection. The so-called “collaborators” were brought before crowds—sometimes in village squares, sometimes inside prisons—where scissors and razors marked them as traitors. The punishment drew spectators of all kinds: men, women, and even children. What should have been moments of justice often turned into scenes of mass spectacle, blurring the line between accountability and vengeance.

Those who took part in these humiliations came from all walks of life. Members of the French Resistance, ordinary citizens, and even officials joined in. For many, it was seen as a necessary act of cleansing the nation of those who had “betrayed” it. Yet, behind the anger was also an unspoken tension—a need to channel collective guilt and frustration after years of occupation and powerlessness.

Researchers later categorized these accusations into three main types of collaboration:

- Political, where women were said to support or assist organizations tied to the German administration;

- Financial, where they profited from business or professional dealings with the occupiers;

and Personal, referring to emotional or physical relationships with German soldiers. - A fourth, rarer category applied to those who had contact with citizens from Axis nations such as Germany, Italy, or Japan. Official records mention 2,315 documented cases of women punished under these definitions, though historians believe the true number was far higher.

Photographer Lee Miller, one of the few journalists to document these events, recalled witnessing one such scene: “I saw four girls being dragged through the streets. I ran to take their picture and suddenly found myself surrounded. The locals thought I was the soldier who captured them. They thanked me, even as others hurled slaps and insults at the girls.” Her testimony captured the chaos of a nation caught between liberation and vengeance—a France trying to heal but also seeking someone to blame.